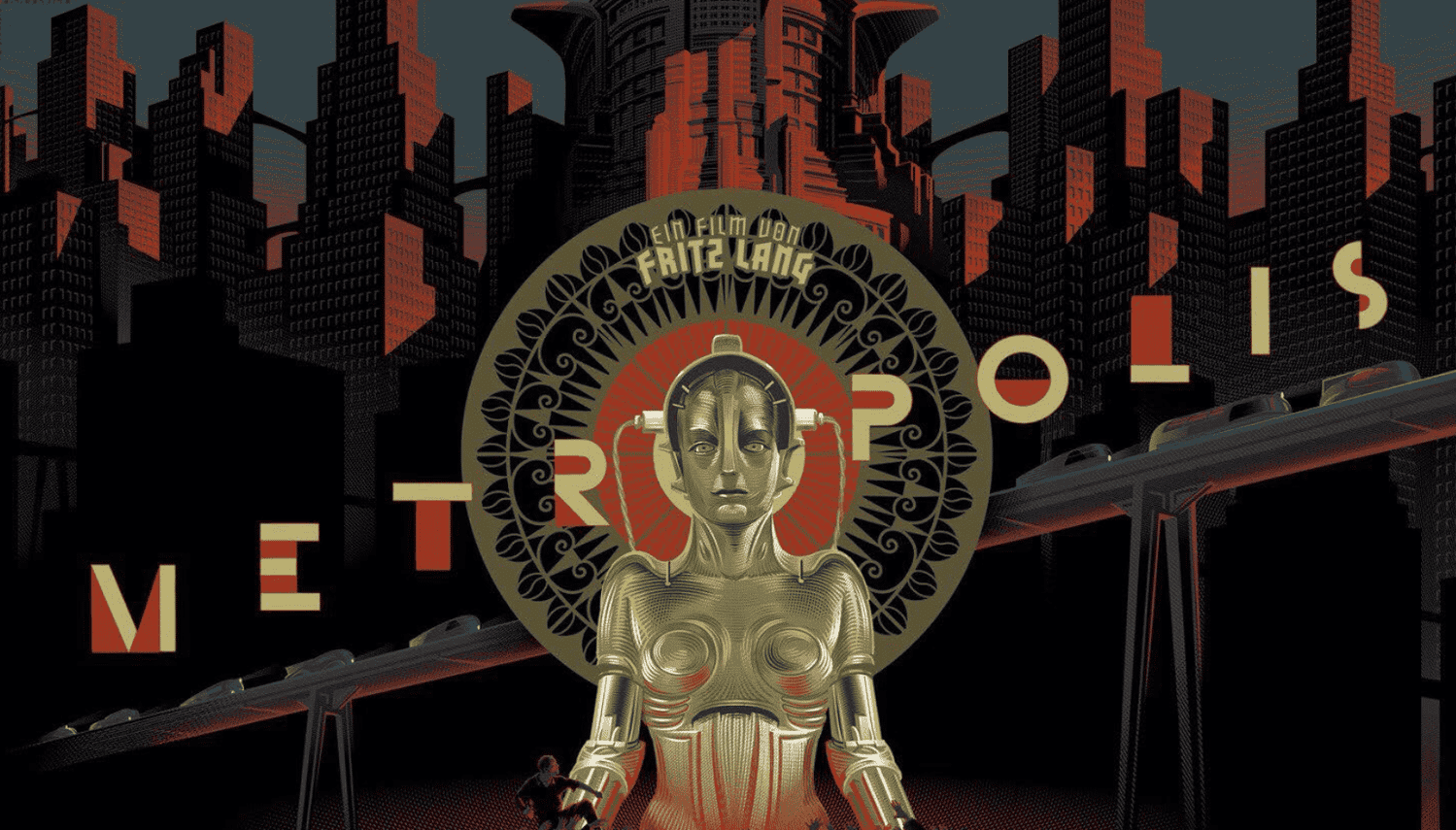

100 years ago, a movie called ‘Metropolis’ imagined 2026

That imagined future has now quietly become the present.

Almost a century ago, Fritz Lang tied his vision of the future to a specific year. His 1927 film Metropolis imagined a vast, mechanized cityscape unfolding in the year 2026. At the time, the date was pure speculation, a distant marker meant to signal progress, power, and anxiety about where modern life was headed.

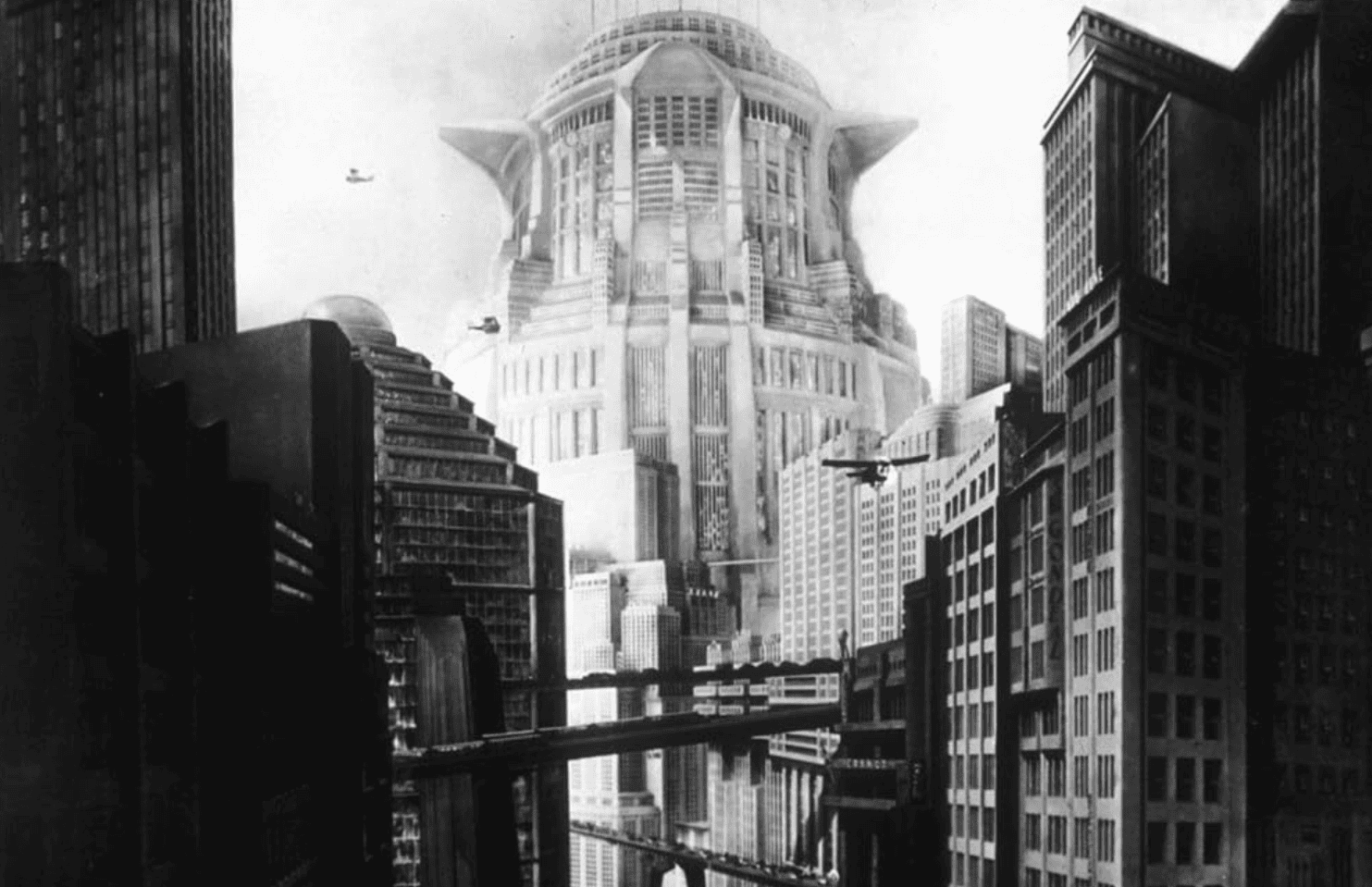

The film depicts a vast, vertically divided city, where an elite class lives among towering skyscrapers while workers toil underground to keep the system running. The film centers on the city’s ruler’s son, Frederic, whose growing awareness of this division fuels the story’s moral conflict.

Now that 2026 is no longer speculation but reality, Metropolis invites a fresh look. It captures the structural tensions that continue to shape contemporary urban life: who benefits from progress, who pays for it, and how technology is changing human relationships as power is concentrated at the top.

The machines in the film are advanced, automated, and visually impressive. However, they don’t relieve people of their jobs. They require constant human intervention and punishment when something goes wrong. In one of the film’s most famous scenes, a factory machine transforms into the god Moloch, devouring workers. This wasn’t meant literally. It was Lang’s way of illustrating how systems can demand sacrifice without openly acknowledging it.

Watching the film today is not a nostalgic exercise. It is a mirror. And like any good mirror, it does not reflect technology. It reflects choices. And if there is one thing that “Metropolis” certainly did not anticipate, it is the degree of elite resistance to any real restoration of balance.

The film bets that extreme confrontation can inspire empathy, that the proximity of collapse can awaken conscience. A century later, this may be its most naive fantasy. Robots, vertical cities, and technological control seem plausible. The idea that economic inequality can be reduced without political conflict – with goodwill alone – sounds even more plausible today than it did in 1927.

Credits:

Images: